We really want to believe that the pleasure of contemplating a beautiful painting or tasting a glass of fine wine depends entirely on the quality. But this is not true.

In 2001, Frederic Brochet from the University of Bordeaux invited 57 wine critics and asked them to comment on the proposed red wine. Brochet picked up a second-rate Bordeaux wine and poured it into two different bottles. One of them was with an expensive label, and another one with the label of an ordinary table wine. The experts praised the “expensive” wine lavishly and criticised the “cheap” one bitterly.

Last year, psychologist Richard Wiseman bought a wide range of wines (from Bordeaux that costs $5 a bottle to champagne that costs $50) and asked ordinary people, not experts, to evaluate them. All the tests were organised so that the price of the samples was unknown neither to the tasters, nor to Wiseman himself. The experiment was attended by 578 people.

Expensive champagne was named as the best one in 53% of cases – that is randomly. Assessing the red wines, 61% of the tasters selected the cheaper Bordeaux as the most expensive wine. A similar conclusion was made during the study in 2008: amateurs found expensive wines less tasty.

The obvious question is if most people do not see the difference between the Château Mouton Rothschild ($700-2000) and Heritage BDX ($35), why are we so obsessed with these premier cru? Why not choose what is cheaper?

It’s all about the sensory limitations of the brain. Our expectations are more important than the contents of the glass. Trying wine, we do not value the quality first and then the price. We estimate everything simultaneously. If you know that the wine is cheap, you will treat it as cheap. And if you think it to be expensive, you will perceive it as expensive.

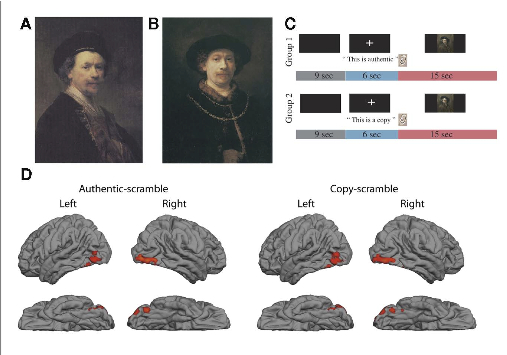

Similar processes occur in the head while evaluating works of art. In 2011, a team of scientists from Oxford invited 14 volunteers, who were familiar with the works of Rembrandt, but not experts. The conditions were as follows: the volunteers would be shown 50 paintings by Rembrandt, and before each demonstration the organizers would tell the participants if it were the original or a copy.

The paintings included portraits. A half of them were painted by Rembrandt, and the rest were created by his disciples and followers. Each portrait was shown for 15 seconds. The trick was that when showing the originals, half of the volunteers were told that it was a copy, and when the copies were shown, they were presented as originals. The people without artistic education were not able to distinguish the original from the imitation: in both cases, the same areas of the brain were involved.

Despite the high similarity of the data, the scientists did manage to find a particular response to the original (regardless of whether they really were the originals or the participants of the experiments were just told so). Some activity occurred in the orbitofrontal area of the brain, responsible for the perception of rewards, pleasures, and financial benefits. The quality of the painting made no difference. Important was only the conviction that it was a valuable product.

Analysis of the responses to copies (when the people were told that it was an imitation) gave another valuable conclusion. When shown copies, the volunteers demonstrated activity in the frontal pole area and precuneus cortex. This is a sign that people were looking for flaws in the paintings. They already had the diagnosis (“Fake!”), and they just needed a proof of their being right.

All of these studies show that our estimation depends on our prejudices. Something beautiful becomes beautiful only when we know about it. Needless to say that the same is applied to fashion and to the choice of a partner.